The Vermilion Lighthouse is a replica of the original lighthouse that was later moved to Lake Ontario. Known as the "Town of Sea Captains," Vermilion was without a lighthouse for 63 yrs. The lighthouse is located next to Main Street Beach in downtown Vermilion, Ohio.

Vermilion, Ohio straddles a river of the same name as it empties into Lake Erie, and it has a past as colorful as the clay for which the river was named. Once known as the “city of sea captains,” the city was a popular drop-off point for illegal liquor from Canada during the days of Prohibition. The city has been home not only to many captains and sailors, but also to an amazing lighthouse story that spans two centuries and two Great Lakes.

Vermilion, Ohio straddles a river of the same name as it empties into Lake Erie, and it has a past as colorful as the clay for which the river was named. Once known as the “city of sea captains,” the city was a popular drop-off point for illegal liquor from Canada during the days of Prohibition. The city has been home not only to many captains and sailors, but also to an amazing lighthouse story that spans two centuries and two Great Lakes. Inhabited by the Erie Indians as early as 1656, Vermilion had grown large enough by the mid-nineteenth century for its harbor to warrant government maintenance. In 1847, Congress appropriated $3,000 to build a lighthouse and prepare the head of the pier on which it would be built. Before 1847, the people of Vermilion had constructed their own navigational aid: wooden stakes topped with oil-burning beacons at the entrance of the harbor.

Inhabited by the Erie Indians as early as 1656, Vermilion had grown large enough by the mid-nineteenth century for its harbor to warrant government maintenance. In 1847, Congress appropriated $3,000 to build a lighthouse and prepare the head of the pier on which it would be built. Before 1847, the people of Vermilion had constructed their own navigational aid: wooden stakes topped with oil-burning beacons at the entrance of the harbor.By 1852, both the lighthouse and the pier were in need of repair, a project that cost $3,000. Seven years later, in 1859, the lighthouse was rebuilt at a cost of $5,000. The new lighthouse was made of wood and topped with a whale oil lamp. The lamp’s flame was surrounded by red glass, resulting in a red beam that, with the help of a sixth-order Fresnel lens, was visible from Lake Erie. A man from the town looked after the lighthouse, lighting the lamp each evening and refueling it each morning.

Though the 1859 light was functional, it was not sturdy enough for long-term use. Both time and the lake’s elements took their toll on the wooden lighthouse, and by 1866, Congress had appropriated funds to build a new light, this time out of iron, on the west pier. The lighthouse was designed by a government architect and cast by a company in Buffalo, New York. A home for the future keeper was purchased in 1871, six years before the iron lighthouse was installed.

To cast the lighthouse, the ironworkers used sand molds of three tapering rings, octahedral in shape. The iron they used was from unpurchased Columbian smoothbore canons, obsolete after the Battle of Fort Sumter. As noted by Vermilion native Ernest Wakefield, “The iron, therefore, of the 1877 Vermilion lighthouse echoed and resonated with the terrible trauma of the War Between the States.”

To cast the lighthouse, the ironworkers used sand molds of three tapering rings, octahedral in shape. The iron they used was from unpurchased Columbian smoothbore canons, obsolete after the Battle of Fort Sumter. As noted by Vermilion native Ernest Wakefield, “The iron, therefore, of the 1877 Vermilion lighthouse echoed and resonated with the terrible trauma of the War Between the States.”Once the ironworkers in Buffalo had completed the casting of the lighthouse and ensured that all parts fit together correctly, the pieces of the lighthouse were loaded onto barges in the nearby Erie Canal. Hauled by mules, the barges reached Oswego, New York, in two weeks. From there, the lighthouse was transferred to the lighthouse tender Haze. The Haze, a steam-powered propeller vessel, departed Oswego on September 1, 1877 and headed west for the Welland Canal, where a series of 27 locks raised the boat to the water level of Port Colborne and onto Lake Erie. One must wonder why this circuitous route was taken when Buffalo, where the tower was cast, sits right on Lake Erie.

On its way to Vermilion, the Haze stopped at Cleveland Harbor, where it took on the lighthouse’s lantern, lumber and lime for building the foundation, and a crew to raise the lighthouse. Also loaded was a fifth-order Fresnel lens, which had been shipped to Cleveland by train. All that is known about the lens is that it was made by Barbier and Fenestre of Paris, France. Whether it was ordered specifically for the Vermilion lighthouse or recovered from the Erie Harbor Lighthouse, no one knows.

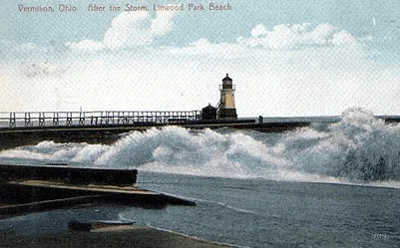

One day later, the Haze arrived in Vermilion. It took several days to prepare the foundation, and once it was in place, the crew used the derrick on the Haze to lift the bottom ring of cast iron and place it on the foundation. After the ring was bolted down, the successive tapering rings were put into place and bolted to each other. Then the pediment and lantern were added. The Fresnel lens and oil lantern were installed later. Once completed, the tower measured 34 feet high. It stood at the end of the pier with a long 400-foot-long catwalk running above it. This allowed the lighthouse keeper to travel between the light and the mainland when large waves crested over the pier. One such lightkeeper was Captain J. H. Burns, who lived in the home purchased by the government in 1871. From this home on the corner of Liberty and Grand Street, he would walk each night to hang the lantern inside Vermilion’s lens. He would also wash the windows around the prism twice a week.

Initially, oil for the lantern was stored in the keeper’s house. It was not until 1906 that an oil shed, accommodating 540 gallons, was built just south of the lighthouse. The lamp was converted to acetylene in 1919, and then eventually into an electric beacon. Its white light would blink one second on, seven seconds off. Ultimately, it was replaced by a steady red beam.

The 1877 lighthouse performed its duties faithfully for over half a century, shining its light for both commercial and pleasure boats. During this time, it was moved closer to the end of the pier (25 feet from the outer end), and survived multiple collisions with watercraft. Eventually it was put under the care of Lorain Lighthouse’s assistant keeper, and in the early 1920s, the Vermilion keeper’s home was sold to the local Masonic Lodge.

The 1877 lighthouse performed its duties faithfully for over half a century, shining its light for both commercial and pleasure boats. During this time, it was moved closer to the end of the pier (25 feet from the outer end), and survived multiple collisions with watercraft. Eventually it was put under the care of Lorain Lighthouse’s assistant keeper, and in the early 1920s, the Vermilion keeper’s home was sold to the local Masonic Lodge.In the summer of 1929, Theodore and Ernest Wakefield, teenagers at the time, noticed that the Vermilion Lighthouse was leaning toward the river. Most likely, the lighthouse pier had suffered damage in an icy storm earlier that year. The Wakefield boys reported what they had seen to their father, Commodore Frederick William Wakefield, who contacted the U.S. Lighthouse Service in Cleveland. The U. S. Corps of Engineers came to Vermilion and determined that the light was indeed unstable. Within a week, the lighthouse had been dismantled. In its place, a steep-sided 18-foot steel pyramidal tower was erected. The new structure, called a "functional disgrace," continued to shine a red light, but since it was automated, no lighthouse keeper was needed.

Commodore Wakefield offered to purchase the old lighthouse and move it to his property, Harbor View, but his request was denied. Instead, the cast-iron pieces were loaded up and hauled away. The residents of Vermilion were sad to see their beloved lighthouse go. No one told them what the fate of the old lighthouse would be, and its whereabouts were unknown until many years later.

Ted Wakefield, one of the young men who had noticed the lighthouse leaning in 1929, had very fond memories of Vermilion’s past and its lighthouse. As an adult, he put his efforts into encouraging downtown Vermilion to maintain its historical 19th century appearance. His childhood home, Harbor View, was donated to Bowling Green State University and later sold to the Great Lakes Historical Society. Built of gravel from Lake Erie in 1909, the old house became the main structure of the society's Inland Seas Maritime Museum. This gave Ted an idea. He decided that a replica of the 1877 lighthouse would be the perfect complement to it.

Ted spearheaded a fund-raising campaign to build the new lighthouse. Funds were raised by mailing out brochures, writing articles in the local paper, and collecting donations at the museum. By 1991, Ted and his fellow fund-raisers had collected $55,000---enough to build a 16-foot replica of Vermilion’s 1877 lighthouse. Architect Robert Lee Tracht of Huron prepared the plans, which were approved by the city, county, and state authorities, but only after a long delay. Even the U.S. Coast Guard approved the plans for making the light a working lighthouse, right down to its steady red light. Again, a company in Buffalo fabricated the lighthouse.

Ground was broken for the new lighthouse on July 24, 1991, by Mayor Alex Angney. The 25,000-pound base of the replica lighthouse, measuring 15 feet in diameter, was brought to Vermilion on a flatbed truck. Cranes were used to place it onto the foundation. According to rumors, before the base was attached to the foundation, an 1877 gold piece was placed under the vertex of the octahedron that would point true north. It seems only fitting that a piece of 1877 be part of the new lighthouse’s foundation.

The tower was raised in less than three hours on October 23, 1991. The lantern and roof were attached the next day, and a fifth-order Fresnel lens (owned by the museum) was mounted. The tower was electrically wired, and an incandescent 200-watt lamp with Edison-base was installed. A red glass cylinder surrounded the lamp to make the replica complete. The new Vermilion Lighthouse was dedicated on June 6, 1992, and is still operational today. It serves not only as part of the museum, but also as an active aid to navigation.

Shortly after their new light was built, the residents of Vermilion learned what had become of their original lighthouse. Amazingly, the structure had not been destroyed after its removal. In fact, it was still shining, and had been for the last 59 years.

Shortly after their new light was built, the residents of Vermilion learned what had become of their original lighthouse. Amazingly, the structure had not been destroyed after its removal. In fact, it was still shining, and had been for the last 59 years.Once the lighthouse had been dismantled in 1929, it was transported to Buffalo, New York, where it was renovated. Six years later, in 1935, the lighthouse was given a new home and a new charge---on Lake Ontario. Sitting off Cape Vincent at the entrance to the Saint Lawrence Seaway, the Vermilion Lighthouse was given a fifth-order Fresnel lens and renamed East Charity Shoal Lighthouse. The light remains an active aid to navigation, with its modern optic (installed in 1992) displayed at a 52-foot focal plane.